The Sand Snakes of Colares

Vines growing in the sand? The unique ungrafted vines of DOP Colares snake their way down the sand by the ocean, producing rare grapes and ageworthy wines.

It was a cold, drizzly November day when I set out from Lisbon for my rendezvous with the unique sand ‘wines’ of Colares.

Colares is an appellation near the coast of Portugal, a few miles north of Lisbon, in the shadow of the towering hills of Sintra. Gradually and inevitably swallowed by the urban sprawl surrounding it, there is now a brave effort to reclaim its place among the heritage wines of Portugal.

Vines in the sand

Many wine regions around the world abut the ocean but the vines of Colares are a mere 200 metres from the Atlantic (you can hear the waves roar from the vineyards) and are unlike any other. Here are no pristine rows of neatly-trained vines: Colares grows its vines on the sand. If you are thinking of the basket-trained vines on the shores of Santorini, know that the similarities end here. In Colares, the vines trail lazily across the golden sand seemingly untrained and almost wild, a back-breaking job to plant, tend to and harvest – always and only by hand.

Our tasting at the Adega Regional de Colares: Ramisco by candlelight! Image: Varun S.

The strong ocean wind keeps moisture away, saving the vines from fungal disease, but also can shut down vine growth. So, straw and bamboo matting, stone walls and banks of fruit trees are used to shelter the vines from the ocean.

A tiny appellation

There has been immense shrinkage of the area under vine. Today, Colares stands at a mere 20 hectares of vines instead of 1000 hectares a century ago. While the DOP has shrunk over the years, some new vineyards have been planted recently and a handful of passionate viticulturists are now working to preserve this unique land; Colares might be lesser known than the mighty Douro Valley but nonetheless it constitutes an important part of Portuguese winemaking heritage – references go back to the 13th century – and heritage must be protected.

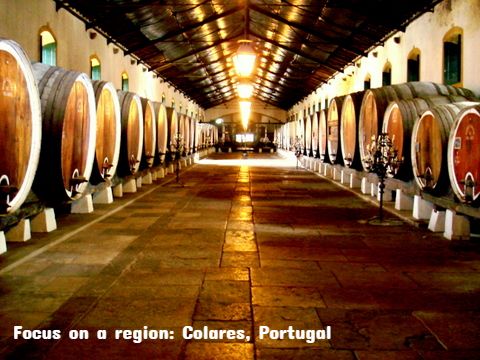

“Sand is important for our vines,” assistant winemaker Ana Sofia Caldeira tells me as I enter the massive white-tiled structure housing the wines of Adega Regional de Colares, a giant cooperative which was mandated to vinify all the grapes of Colares from 1934 until 1994, and still does for many producers.

Sand is in fact the very reason why the vines have survived, free of the dreaded phylloxera scourge which devastated the vines of Europe in the late 19th century. “Over 80% of the vines in Portugal were affected during the outbreak but we (Colares) were protected from it because of the sand.” Phylloxera, a microscopic aphid that attacks the roots of the vines, does not like sand and cannot thrive in it. Ergo, the very factor which makes Colares’ vines un-pretty and labour-intensive is also its savior. Many of the vines are ungrafted, over 100 years old, and propagated by selection massale.

That is not all. The golden sand warms in the day time, absorbing the heat from the sun and reflects it back at night, allowing the grapes to ripen fully. The misty mornings and cool rainy days allow the grapes retain their acidity and singular flavor profile.

Rare grapes

The vines are propped up on sticks in summer to avoid sunburn

The second fascinating fact about Colares is the grapes used for their wines. White wines are made predominantly from Malvasia of Colares (appellation rules mandate a minimum 80% in the blend). “This grape probably came from France, but has adapted to the sandy soil here,” says Ana Sofia. Portugal has as many expressions as 12 expressions of Malvasia, she explains, but other Malvasia grown in the interiors of Portugal are the regular varieties, grafted on to American rootstocks post-phylloxera. Malvasia of Colares is exclusive to the DOP.

The dominant black grape of Colares is Ramisco, small and thick-skinned (Alentejo’s Trincadeira is a sibling, says Jancis Robinson). Other grapes in the appellation include Arinto, Galego Dourado and Jampal (rarely found white grapes). Ramisco is the star, however, planted in deep trenches in the sand so the roots can burrow through to the clay soils deep beneath the surface. “The roots are over three metres deep,” explains Ana Sofia. Wines from Ramisco have a searing acidity and high tannins. Alcohol and body tend to be on the lower side. They are not suited for early drinking, becoming approachable after several years in the bottle, where they develop tertiary notes of mushroom, earth, smoke and cedar.