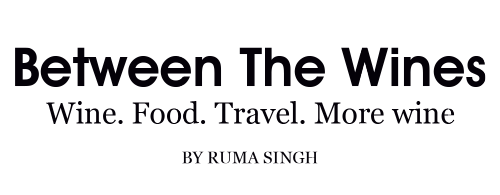

The legendary winemaker behind the famous ‘No barriques, no Berlusconi’ dictum created a legacy of fine, pure winemaking which is alive and thrives even today…I discover the raison d’etre behind Barolo’s iconic Bartolo Mascarello

It’s for good reason that Barolo known as the wine of kings. It’s certainly not a wine for those looking for a quick, easy quaff. The DOCG wine from Italy’s Piedmont has been called a ‘meditative’ wine by its multitude of fans, a kind word for a wine that can takes ages to unfurl its bounty and become approachable in the glass. A light-coloured red wine made from the region’s native Nebbiolo grape, it is late-harvested (October, when most other grapes are done), and makes a wine that, after spending a minimum of long three years in traditional large botti (25 hl barrels) can stun with its sheer power and structure, or overwhelm with its strong tannins and acidity. Not for the faint-hearted or sugar babies. This is a majestic wine from a region of proud winemakers.

Modernist, traditionalist, and the heart of Barolo:

This was Barolo as it once was. In the 1960s and 70s a new generation of Barolisti decided to tweak their traditional winemaking to make a wine that’s earlier, easier to drink and tons more approachable. The botti and extended maceration (capello sommerso method or submerged cap ) gave way to shorter maceration periods and French barriques, where the wine could soften faster in contact with the wood. The ‘new age’ winemakers led by Renato Ratti, Angelo Gaja and Elio Altare were known as the modernists, often making single vineyard cru wines, another contrast to Barolo’s traditional multi-vineyard blend. The traditonalists headed by Bartolo Mascarello, Giuseppe Rinaldi and Giovanni Conterno continued to be steadfast to the time-honoured methods of crafting their iconic Barolos.

Today, both styles of Barolo have their followers and their winemakers coexist in harmony in the region.

The traditionalist icon:

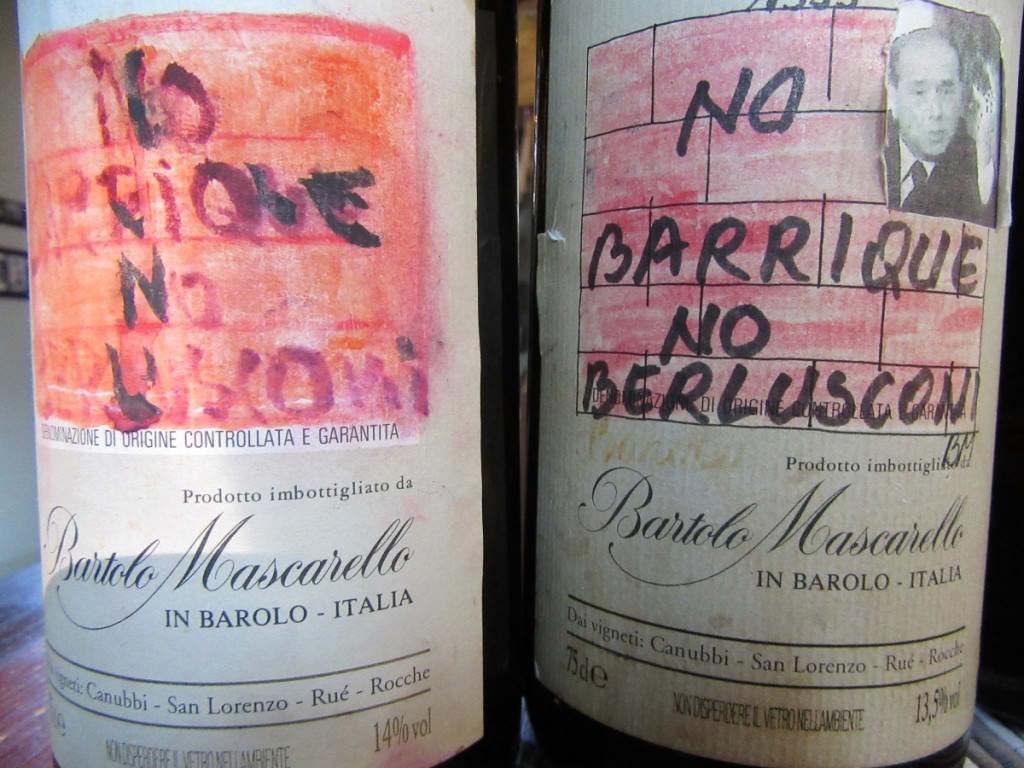

With this background in mind, I began chalking out my all-too-short trip to Piedmont. It was on the cusp of the truffle season (October), and I wanted to try both forms of Barolo – traditionally-made and the newer style. On the top of my list of traditionalists was the historical winery of Bartolo Mascarello. Often called the ‘elder statesman’ and ‘towering figure’ of traditional Piedmont winemaking and self-described ‘the last of the Mohicans,’ Bartolo, who died in 2005, was the 3rd generation winemaker in his family after father Giulio and grandfather Bartolomeo. He had left his legacy in the capable hands of his daughter, Maria Teresa, the current winemaker (her first vintage was 1993). These were no easy shoes to fill.

A winery this notable and revered should be easy to find in the tiny town of Barolo, right? Not so. It took me 3 weeks of suspense and botti-loads of patience to finally make contact with the winery and fix a visit. Bartolo Mascarello has no website, and Maria Teresa has no computer, not even an email address. Mascarello remains truly old school.

It was a sunny afternoon in the small village of Barolo as we drove in. Harvest was in progress in many of the vineyards scattered across the 11 communes that constitute Barolo. Maria Teresa would be busy in the vineyards with her band of merry pickers but I could have a tasting and winery tour, I was told. That was good enough for me. After a stupendous wine-paired lunch in a restaurant overlooking lush vineyards, we strolled down to locate Cantina Bartolo Mascarello.

Chez Bartolo:

No large gates, no impressive nameplate, just a tiny brass bell on a whitewashed wall sandwiched between a café and a side street. Impossible to believe, but yes, here it was – the simple domaine of Bartolo Mascarello, home to Maria Teresa and the winery/cellar all rolled in one. We walked into the tasting room, which felt more like a friendly Italian kitchen. No gleaming spittoons, no racks of bottles, lines of glasses. Just 6 (very lucky) people around a wooden table. At the head was Alan Manley, Maria Teresa’s right hand and translator/manager, a true American in Italy, who had come lured by its fine wine and had lost his heart to the country.

Four out of the 6 others present had been there before but were back, anxious to catch up on the latest on Bartolo’s wines and harvest news (this was their 98th harvest in progress!). “When Giulio, Maria Teresa’s grandfather, started the winery it was 4 hectares in all,” said Alan, deadpan. “Now it’s a whopping 5 hectares.” It’s a testament to Mascarello’s steadfast commitment to their roots that they refuse to expand or modernize to grow volumes. “We make 32,000 bottles if it’s an abundant year. We work traditionally in the vineyards and cellars. We are not interested in crus, but follow the assemblage method. We are not chained to the number of bottles produced, and every year the wines are different – as they should be. We are not making Coke, after all,” he says.

Vinification takes place in the (relatively) tiny basement winery, in cement tanks and Slavonian oak botti, without any commercial yeast, stainless steel (“It can cook your wine.”), punchdown or temperature control. The trick, adds Alan, is simply picking the best grapes at optimum readiness, and letting the fruit and nature do their work. “We want the gentlest extraction. Each wine will find its equilibrium point.” The maceration is at least 30-35 days, sometimes longer. “The wine tells us when the skins are talking back. In 2010 it was 56 days, while in 2013, it was just 21 days. The wine decides,” says Alan.

The tasting:

Among Bartolo Marcarello vineyards are in the super-prestigious Cannubi (1 hectare), San Lorenzo, Rue and Rocche in La Morra. They make just one expression of Barolo, sold in the 4th year after it is made, and a great value bright, juicy rounded Dolcetto. They also make a tiny quantity of their Freisa, 1200-1800 bottles a year. Alan opens a bottle of Bartolo Mascarello Langhe Freisa 2014 for us. This was something new for me: a red grape that’s neither a spumante nor frizzante even, a tiny fizz and distinct aromas of fermentation and sour cherries, strongly tannic. “People love it or hate it,” Alan acknowledges. I must confess the jury’s still out on that one for me.

The Bartolo Mascarello Barbera d’Alba 2014 from their San Lorenzo vineyards, was what Alan termed a ‘simple wine,’ bright, lovely with distinct acidity but low tannins. Loads of chocolate and black fruit and a whopping 14.5% alcohol.

Finally, the Bartolo Mascarello Barolo 2012. A difficult year, climate wise, said Alan. “Because of hail we got 20% less wine, but the taste was lush, pure, aromas of strawberries. In another 5 years, it will develop more dark fruits. Drink it 20 years later.” I found, a hint of rose, spices and herbs with a hint of the supple tannins should I have waited another 10 years. Bartolo’s Baroli are considered rich, sinewy and intense. This was still a baby in Barolo-years but still immensely approachable.

I didn’t taste it, but the winery also makes a Nebbiolo Langhe (declassified Nebbiolo from Barolo-designated vineyards, shorter maceration). An absolute steal.

The winery:

We meander below to the winery, Alan leading the way. The dusty cellars were dotted with little nuggets of viniferous history: bottles dating back to 1929, and some precious collectors pieces, with labels hand-drawn by Bartolo in his last years when wheelchair-bound, he picked up his paints and pastels instead. His “No Barriques, No Berlusconi” labels are famous – the two no-nos which to his mind spelled banality and blah-dom (The labels resemble graffiti on a wall, with a partially obscured photo of infamous former Italian prime minister Silvio Berlusconi). Today, those bottles with their whimsical, hand painted labels cost a fortune in auction, but he “made them for his own enjoyment” not to make a statement,” says Alan.

Dollops of integrity:

The meagre 1250 cases of wine that the cantina produces even today means allocations are miniscule, Alan tells us stories of how some of the world’s big wine merchants write in begging for just a few bottles more. But Maria Teresa won’t budge. Bartolo’s Barolo is rare, so much so that it is now a cult wine, appreciated even more for being made with a singular integrity. “Some customers even bequeath their allocation to their next generations in their wills, and Maria Teresa always honours them first, rather than sell at higher prices to bigger buyers. She has no greed to expand to new markets, she’s made a choice to stay small. We are tiny, very tiny. I have 15,000 bottles of Barolo and 200 magnums to divide among our loyal buyers around the world. But Maria-Teresa has chosen to keep her father’s legacy alive.”

The meagre 1250 cases of wine that the cantina produces even today means allocations are miniscule, Alan tells us stories of how some of the world’s big wine merchants write in begging for just a few bottles more. But Maria Teresa won’t budge. Bartolo’s Barolo is rare, so much so that it is now a cult wine, appreciated even more for being made with a singular integrity. “Some customers even bequeath their allocation to their next generations in their wills, and Maria Teresa always honours them first, rather than sell at higher prices to bigger buyers. She has no greed to expand to new markets, she’s made a choice to stay small. We are tiny, very tiny. I have 15,000 bottles of Barolo and 200 magnums to divide among our loyal buyers around the world. But Maria-Teresa has chosen to keep her father’s legacy alive.”

PS: We had no hopes of buying a bottle – there were none available ex-winery. But while chatting with Alan Manley as we left, he said, do try this little wine shop around the corner. You might find a bottle there if you’re lucky. We hurried around to La Vite Turchese. What an absolute treasure of a wine shop/enoteca – wooden racks lined with the best of Barolo along with other iconic Italian winemakers. A perfect place to sip, browse and explore…..Yes, I bought my bottle of Bartolo’s Barolo!

Address: (Visit by appt. only), Via Roma, 19, 12060 Barolo Province of Cuneo, Italy

Phone: +39 0173 56125