It’s not really a surprise that many people around the world are still quite unaware that India can make quality wine. I still often encounter astonished reactions during my travels – again not surprising because stereotypes of India in some parts still include elephants, flying carpets, poverty and heat – a lot of heat. Wine in India? Is it possible, I occasionally get asked. This is followed by a fascinated interest…tell me about Indian wines, the terroir, the grapes… and so on.

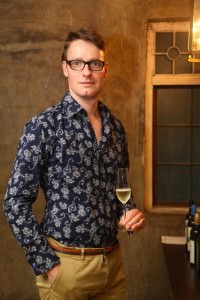

The curiosity and interest, along with the very visible gap in the market are some reasons why Peter Csizmadia-Honigh left his job at the Institute of the Masters of Wine (IMW) after a long stint as education manager to embark on writing his definitive tome on Indian wines called The Wines of India: A Concise Guide. “I just had to do it,” he told me during a visit to Bangalore to launch his book. “Wine production has been dynamically growing in India, but despite the qualitative changes, there is little known about Indian wines. Every country wanting to be on the world map of wine has got to have guides and books, helping consumers and the wine trade alike. Practically, there was a gap in the market, which I spotted and wanted to fill.”

There’s no getting away from the fact that Indian wines are still regarded very much as an exotic curiosity in the established wine world. “There’s no real understanding about what Indian wines are really like. There’s so little Indian wine exported even now, and very little supporting information from authorized bodies to help wine professionals understand it. Though the last 5 years have seen quality of Indian wine rise sharply – some wines are still dire, while others are not.”

One cannot agree more – the young wine industry functions fairly loosely as a whole, and there is no concept of terroir or substantive research to help producers from outside the ranks, nor regulations to enforce quality compliance. Which is why some pockets of dedicated, self-regulated producers are producing very good award-winning wines through their own efforts and resources, while others continue to flounder. To produce quality wine in India, you need patience, tenacity and deep pockets, as well as an abiding love for wine itself.

So for Peter, the writing of the book became something of an epic journey. The first three months were spent in research which often proved frustrating. “Sometimes my phone calls were answered by people speaking in Hindi or Marathi, and I’d try to explain I was a wine writer from abroad…. I achieved so little compared to what I wanted to. I was also a book production virgin, and it was hard pulling all the elements together – design, cartography, fact-checking.” The entire exercise took him 15 months, starting July 2014. In conjunction with the project, he had to keep working on his own vineyards in Hungary (Royal Somló Vineyards). Finally, in October 2015, the book was finally launched: it featured 50 Indian wine producers, 400 Indian wines spread over 452 pages with 11 detailed maps. “It helped that the people from the industry were so hospitable and opened their doors and their bottles to me,” he said.

Having had the rare advantage of being able to access inside information combined with the objectivity of a bird’s eye view on the industry so to speak, his impressions interested me. “It’s difficult to draw a parallel,” he said when I ask him which country India most resembles in its wine journey, “Markets everywhere are different. And you need to disregard a large chunk of the population if you’re sizing the Indian market, because of the high government taxes and duties which makes wine here expensive. So the government needs to come to its senses – the unsustainable system of duties, taxes and regulations puts huge pressure on the tiny Indian wine industry. Again, wine must not be demonized publicly, it must be made more accessible, more affordable – that will help to spread wine culture. Your advantage is that you have a very young population compared to Europe, and India is on a fast track as a country. The potential of the country as wine consumers can be unleashed, but a lot still needs to be done. There are challenges too – many Indians do not drink, and there also exists a well-established whisky culture.” A stellar example of quick success close to home is that of Hong Kong, where reducing duties to zero helped it becomes the Asian region’s most important market in a very short time, he points out. So, wine education, having a glass of wine with a meal, and restaurants promoting wines with pocket-friendly wine promotions are some factors which would go a long way to help. As would if the industry came together to work towards the common goals.

A key part of our discussion was on the need for regulations to guide and sustain the young Indian wine industry – putting into place guidelines and regulations which already form the backbone of quality winemaking in established winemaking countries across the world. This is what Peter had to say:

“Regulation is key to the development of the Indian wine industry, however, regulations need to facilitate rather than suffocate the industry, so the Government of India has a lot to do to live up to the ‘unobstacle’ mantra of the Prime Minister. There are two major areas of regulations that need to be tackled in India.

Firstly, on the production side regulations need to be put in place to ensure quality (e.g. permitted agrochemicals, production methods, QA and QC requirements, food safety, etc) and, therefore, protect the consumer. This is really a technical aspect and I do not believe defining appellations are the way forward for India. What if a businessman wanted to set up in Himachal Pradesh, but the regulation did not list it as an ‘appellation’? Of course, if we mean ‘appellation’ as not allowing the use of Bijapur fruit in wine labelled as ‘Nandi Hills’, that would be good and again it would protect the consumer. However, it is more to do with the origin of the fruit, rather than defining ‘appellations’ in the European sense.

“Secondly, there is the commercial aspect of regulation: simplifying taxes and duties, licensing, trading and importing. It would be hugely important that this is done pan-India and not state by state, so there is uniformity, which makes it easy, simple and cost efficient to operate across the country. The reality, however, is that wine is a small drop in the ocean of the alcoholic drinks industry and as many member states of the Indian Union are hugely dependent on deriving their income from alcohol duties, it will take a very determined Government of India to solve the problem by either lifting wine out of the general alcohol regulations or taking away alcohol from state governments.

“Lastly, here’s a warning and a request. If India starts to regulate, please involve the industry so that the regulatory environment will work well; and remember it is not possible just to copy templates, India as a young and sub-tropical winegrower with a young consumer culture has special considerations to take into account for the regulations to work in India’s interests.”

Peter Csizmadia-Honigh will be launching Wines of India: a Concise Guide in London on 19 April 2016 at the Vintners’ Hall, 68 1/2 Upper Thames Street, London, EC4V 3BG. This will be accompanied by a tasting of wines from 10 Indian wine producers.

For more information on the book and to buy a copy, go to http://thewinesofindia.com/